Science of Cheesemaking: Bacteria, Mold & Yeast

Humans made cheese long before we understood science. Fortunately, our understanding of science has come a long way since.

Essentially, cheesemaking is the same back then and now: milk is turned into cheese through a series of steps that control its fermentation process.

To understand the science behind cheesemaking better, let’s start with the taste and smell of cheese…

>> Also read: The Science of Cheesemaking: A Journey from Milk to Artisanal Delight

Where Does The Taste of Cheese Come From?

It comes from three microorganisms: bacteria, molds, and yeasts which are developed and formed during the affinage process. Click here to have a better understanding of Affinage

| Microorganism | Description |

|---|---|

| Bacteria | Bacteria are naturally present in milk, but they can also be added during the cheesemaking process. In the world of cheese, there are three types of bacteria: lactic acid bacteria, surface bacteria, propionic acid bacteria. |

| Molds | Without a shadow of a doubt, molds are the most popular microorganisms in the world of cheese. Molds often have a negative connotation because people often associate molds with rot and disease. However, they are essential to the existence of all living things… and cheese is a living food. It’s alive! |

| Yeasts | Yeast is a unicellular fungus that permits the growth and fermentation of foods such as wine, beer, bread, and cheese. Different yeasts are added to different foods to achieve a desirable outcome. It is totally up to the maker/producer to understand and execute this step. |

Each of these microbes is unique. They either complement or compete with each other.

Now, let’s start with the first microorganism, bacteria:

1. Bacteria

The presence of one type of bacteria may be a winner in a cheese but a loser in another. This depends on the family of cheeses.

For instance, the bacterium Brevibacterium linens makes some cheeses, such as Livarot and Époisses turn into red-orange color. However, if this same bacterium appears on another cheese from a different family, it can cause a defect.

Pseudomonas fluorescens is another flawed bacterium that creates tinges of fluorescent yellow and a rather acidic taste.

And lastly, the Serratia rubideae forms pink hues in cheese. Although we can smell a slight red-beet aroma, in the mouth, this bacterium lends an unpleasant bitterness.

1.1 Lactic Acid Bacteria

The purpose of Lactic acid is to:

- Acidify milk and curds

- Create the taste of cheese

- Create texture

This bacteria promotes lactic acid fermentation – the transformation of lactose (sugar found in milk) to lactic acid.

Also read: Can I eat Cheese If I am Lactose Intolerant?

1.2 Surface Bacteria

These bacteria thrive and grow in an aerobic and salty environment. It is responsible for the soft interior and the formation of a buttery texture under the rind.

The types of cheeses that contain Surface bacteria are soft cheeses with bloomy rinds or washed rinds.

1.3 Propionic Acid Bacteria

These are anaerobic microbes that grow in the absence of oxygen.

The Propionic Acid Bacteria is responsible for turning lactose (milk sugar) into propionic and acetic acids (fatty acids) which gives the cheese its aroma.

These bacteria are also what caused the holes aka eyes in cheeses like Emmental.

Also read: Why Do Some Cheeses Have Holes?

2. Molds

The purpose of mold in cheesemaking is to:

- Modify the taste

- Create texture

- Form color(s) in the interior of the cheese

Scientifically speaking, a mold is a microscopic fungus that chemically changes the environment in which it grows.

There are literally thousands of molds and not every one is edible. In the world of cheese, there are four prominent ones.

These are the big four:

2.1 Penicillium Roqueforti

A mold that is present in most blue-veined cheeses and plays a crucial role in giving both taste and texture.

Its color varies between gray-blue and light gray.

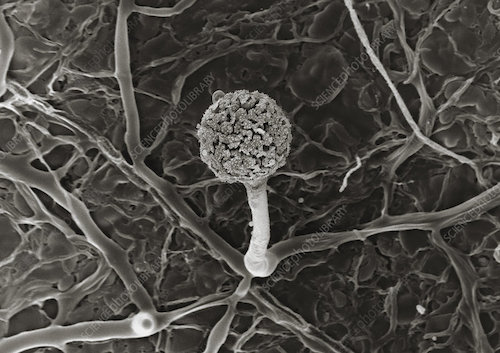

In microscopic view, the emblematic mold of Roquefort looks like a long stem that fans out into ‘bottles.’

2.2 Penicillium Camemberti

This white mold with tinges of blue that darkens over time is responsible for the white surfaces on cheeses.

However, when grows on surfaces, the Penicillium camemberti manifests as a white woolly and filament-like felt hence giving Camembert and Brie their white surfaces.

It gives the cheese a little salty and milky taste.

2.3 Mucor

Mucor aka ‘cat’s hair’ has long gray or black-and-white strands.

It grows on surfaces and is harmless. Nevertheless, the development of this fungus breaks down the rinds of some cheeses.

It is up to the cheesemaker if he wants Mucor present in his/her cheese. When present, it gives a taste of forest floor and hazelnut.

A combination that may have a detrimental effect on some cheeses. For instance, Mucor is welcome in Saint-Nectaire but not on cheeses such as Pouligny-Saint-Pierre.

2.4 Sporendonema Casei

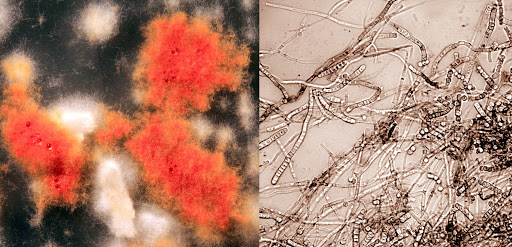

Sporendonema Casei is responsible for the orange spots that appear on the rinds of large cheeses such as Cantal and Salers.

These molds give acidity and typical flavors to the cheese and can be found on the surface of other Tommes in the form of an orange color.

Under microscopic view, this mold has a long and veined filament.

3. Yeasts

The big four of yeasts have intimidating-sounding names like its counterpart, molds.

However, they have relatively simple functions.

These are the big four of yeasts:

3.1 Debaryomyces

Debaryomyces have an abundance of lactose (milk sugar) and lactic acid. They are naturally present in milk and their role is to help make curds less acidic.

They work well with other molds and bacteria to give the cheese its texture and appearance during affinage.

3.2 Kluyveromices

Kluyveromices are natural flavor enhancers, therefore, they play a crucial role in the development of flavor in cheese.

3.3 Geotrichum Candidum

Once considered as molds, today Geotrichum candidum is categorized as yeasts.

It develops in blue-veined cheeses, soft cheeses with washed or bloomy rinds, and uncooked pressed cheeses.

The role of this yeast is to help develop the rinds of cheeses and to give the cheese its flavor (defined as the tactile, taste, and olfactory sensations that occur when we taste foods).

Ultimately, this yeast can also act as a defense against Mucor.

3.4 Candida

When not present in excessive quantities, candida aids in our digestion and lives naturally in our intestines.

They serve to ripen cheeses and make them less acidic.

The Different Types of Fermentation

In combination with lactic acid bacteria, yeasts promote fermentation and therefore the preservation of food products.

In the world of cheese, there are three types of fermentation.

| Type of Fermentation | Comment |

|---|---|

| Lactic acid fermentation | Lactose (milk sugar) is converted into lactic acid. |

| Propionic acid fermentation | The taste, holes (eyes), and texture of cooked pressed cheeses (Comte, Emmental, Beaufort, etc.) are notably due to this propionic acid fermentation. |

| Butyric fermentation | When butyric fermentation occurs, it is considered a defect because it creates a rancid taste in cheese or butter. |

Articles to read: